The Ripple Effect: Being frank about our lingua franca

What language do you speak?

I like to say that at most, I’m bilingual-and-a-half, although it depends on whether my third grade language arts class, my Spanish teacher or my mother is passing the judgment.

One of the languages I count in my comprehension is, obviously, English, which is the most widely studied second language in the world thanks to the expansive former empire of its country of origin. With 1.5 billion English learners in 2015, plenty of aspiring polyglots have it high on their list of languages to learn. Yet on Sunday, the Iranian government banned English-language education in primary schools, citing it as the root of a “western cultural invasion.”

In fairness, this isn’t a drastic blanket ban — English is usually taught in schools after the age of 12, but in recent years, Iranians have pulled that starting date down to a spot earlier in the educational process, sending kids to after-school classes or private tutors if a course isn’t available at their primary schools. Yet standing in the way of early foreign-language education for children, no matter the country or the language at hand, puts these children at a disadvantage.

Now let me put this out there: I am absolutely for the preservation of your native language. It’s reasonable for an Iranian primary school to teach in Persian, because that’s what a majority of Iranians speak. It’s reasonable for an American public school to teach in English, because that’s what a majority of Americans speak. Allowing language attrition to take place is a tragedy — there isn’t a day that goes by where I’m not frustrated that I, an Indian-born immigrant, don’t know my native tongue well enough to pronounce words other than “mom,” “dad” and (maybe) “food.”

After all, a language is never just a dictionary or a dry lexicon turned into towering structures through complicated grammatical rules. A language is the key to a culture. From in-jokes and idioms, gendered nouns to gerunds, your first language is entrenched in your psyche, as seen in countless scientific papers debating the idea that language can gently nudge your perception of the world.

An experiment described in the New York Times gives us an example of this influence: native French speakers wanted a cartoon fork to speak in a female voice; native Spanish speakers expected it to have a masculine voice. The reason? “Fork” is a feminine noun in French (“la fourchette”), while it’s masculine in Spanish (“el tenedor”).

This concept taken to an extreme, then, must also be the reasoning of the Iranian government. Why pull people away from your shared culture and potentially shape everything from how they conjugate verbs to how they process events, all due to the addition of a second language? Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei even argued it this way: English education for children is the “promotion of a foreign culture in the country and among children, young adults and youths.”

But a second language in the curriculum for younger students shouldn’t be treated as an enemy.

We’ve all likely heard the benefits of multilingualism from our language teachers, but they bear repeating. The most obvious benefit is that it facilitates travel, but in the increasingly globalized workplace, knowing someone else’s language could endear you to a client or help you make sense of business trips — unless, of course, you’re an absolute pro at charades. Multilingualism even improves mental flexibility and multitasking skills, what with all the self-control required to not blurt a sentence out in, say, German to your French teacher.

According to the BBC, 60 to 75 percent of people in the world are multilingual, but the issue of monolingualism isn’t actually in nations like Iran — most monolinguals are, in fact, native English speakers. Perhaps it’s the complacency of already having learned the lingua franca of the past several hundred years.

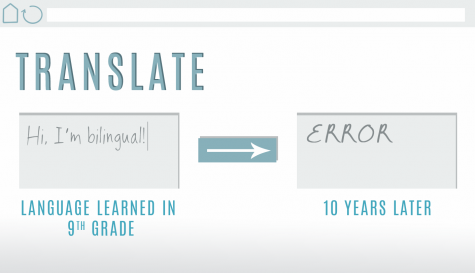

Or, perhaps it’s because we don’t start on other languages at a young age. According to NBC, people learn foreign languages best between their births and the age of seven. Many European countries kick off their schools’ foreign language programs within this time frame, with over 20 requiring students to learn two languages in-class for at least a year, according to the Pew Research Center. Yet only a measly 15 percent of American elementary schools offer such classes, seeing as they usually begin in middle or high school, missing the linguistic window of opportunity by several years. Thus, American students often have low foreign language retention, their knowledge of the lexicon they made hundreds of flashcards for in high school fading rapidly away.

Iran cannot force its children down an ultimately monolingual path, the English learned as teenagers peeling away over time like wallpaper off an old room’s walls, if what’s truly best for them is kept mind. Neither can nations like the United States. The world is growing ever more interconnected: we can either travel to France and frantically flap our arms around in an effort to find out the directions to a hotel, or we can be able to immerse ourselves in the full, rich tapestry of a culture because we understand the words.