We like to think of rights as a footrace.

Imagine it: a cohort of runners, representing countries from around the world, standing at the ready in a stadium filled with wide-eyed watchers. The starter pistol goes off.

Some runners immediately give up. Others end up inches from the finish line, but their audiences heckle them to the point where they stop short of victory. Some complete the dash in record time, even as they play dirty by tossing obstacles into the way of others. And the ones who trip, faltering over those obstacles and falling flat, but eventually limp to the finish line are cheaters, copycats who plagiarized the tactics of the winners.

That’s no race. The human rights 100-meter dash is no metric to judge progress by.

Progress, however, is still being made. Last Thursday, the Indian Supreme Court overturned its ban on gay sex, ruling that Indian members of the LGBT community must be given all constitutional protections, according to The New York Times.

The ban was rooted in Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which was introduced by the British in 1861, during the colonial era, and banned sexual activities “against the order of nature.”

It’s a definite victory for the Indian LGBT community, as no longer can members be blackmailed and bludgeoned with copies of a law from two centuries ago. Indeed, India’s ban was one of the world’s oldest, countering what was a much more relaxed view of the LGBT community prior to the British arrival, meaning the absolute misapplication of Section 377 was all the aftereffects of imperialism condensed into a neat few paragraphs of text.

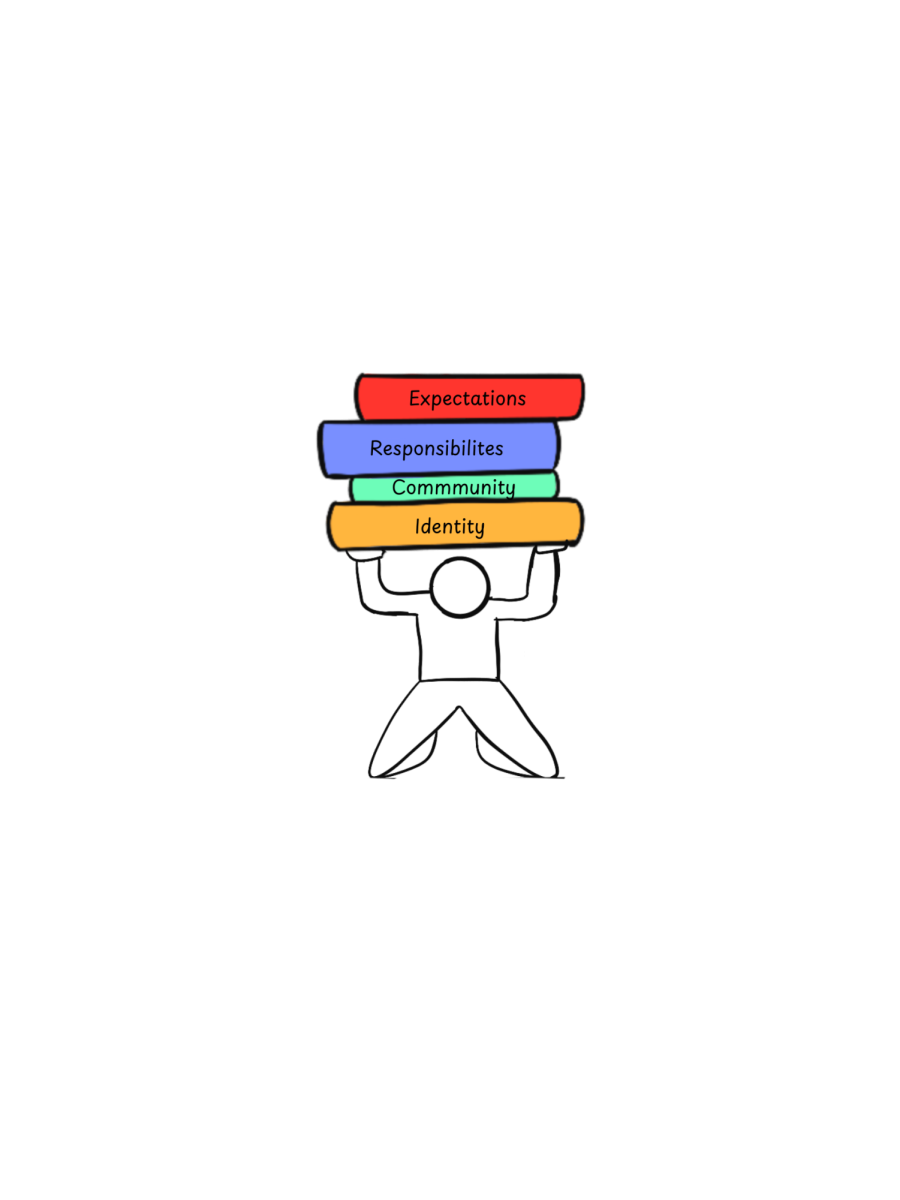

But at the same time, the way to acceptance also requires internal change within India. The chain reaction of conservatism was, indeed, originally kicked off and cultivated by the British, but the burden of changing that collective mindset now is on India’s shoulders.

Certainly, according to the BBC, public opinion in India’s larger cities has been swaying in favor of decriminalization, but “swaying” isn’t quite the support any community feels safe with.

Just from scrolling through comment sections of articles detailing the news, it’s clear that decriminalization hasn’t immediately and irrevocably erased bigotry from people’s minds. Even the text of the Supreme Court’s judgment, arguing that the issue needed to be viewed in terms of “constitutional morality” rather than “social morality,” agrees that society hasn’t thrown its full support behind the LGBT community.

And neither should we expect it do so — the law isn’t a light switch of morality. When gay people, for instance, avoid reporting rapes and assaults for fear of being arrested themselves, as reported by The New York Times, there is a definite culture of fear that’s been cultivated and must still be eradicated.

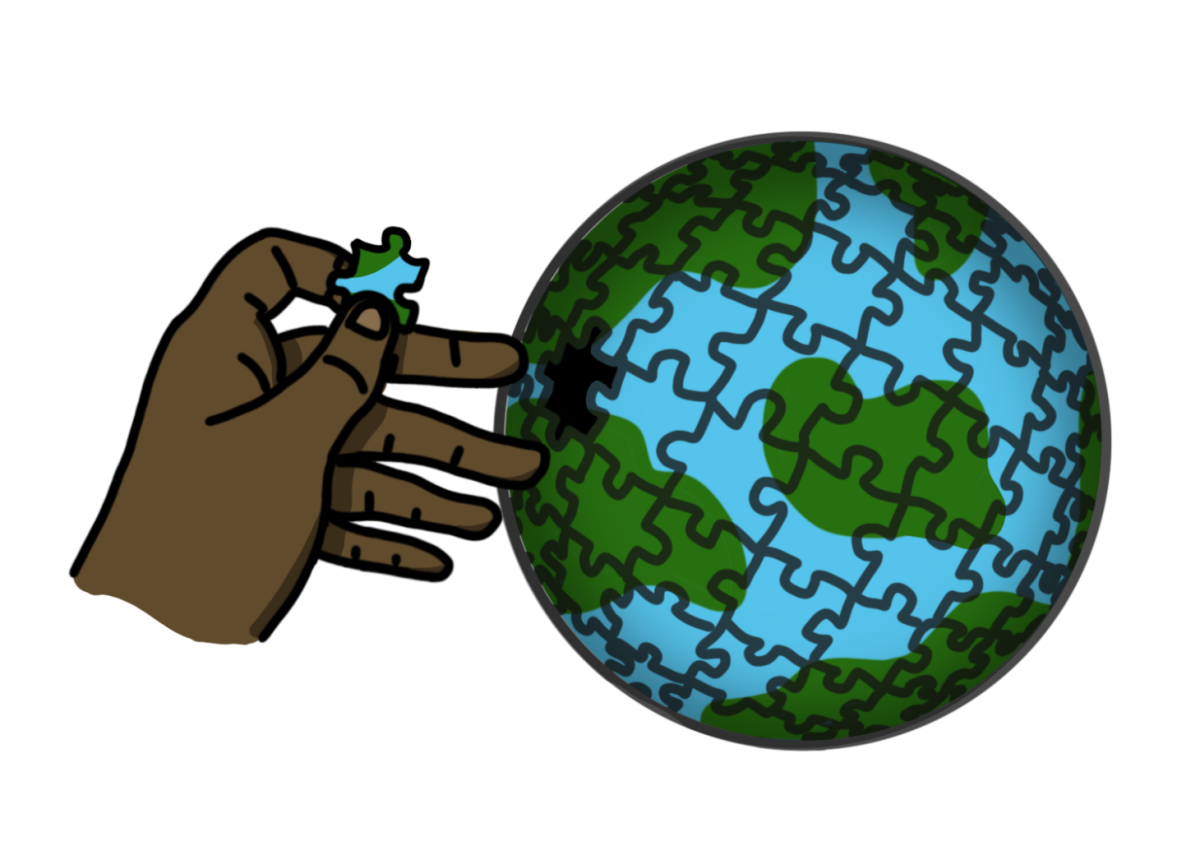

That being said, India’s own ruling has had ramifications elsewhere — at least, in other former British colonies. Barely a week after the Section 377 judgment was weighed in India, a man has filed a challenge against Singapore’s own, mirror-matched, Section 377A, which could mean more positive steps forward in these other countries.

But is all India doing — is all any of these other nations are doing– simply following in the steps of the Western world and finally “catching up” to the likes of America and England? The answer would have to be “no”: it’s taking a different path. Slowed, perhaps, because of the effects of imperialism. But a path forward indeed, in spite of the effects of imperialism.

There are definite similarities in the routes taken, certainly. Both the United States and India, for instance, reemphasized the right to privacy before following up with a judgment legalizing gay sex. For America, the landmark case was 1986’s Bowers v. Hardwick.

For India, the privacy case took place in 2017 — although pundits at the time forecast it as having more of an impact on India’s identity card scheme rather than its LGBT community.

But in other ways, India isn’t taking the beaten road. In 2014, the court ordered the government to allow for a third gender on official forms and to let transgender people be recognized without having to undergo gender-reassignment surgery; a marked difference from other countries that have laid down rights for gay people before they did so for transgender people.

Even in America, to this day, gender-reassignment surgery is required to change one’s gender on birth certificates in a majority of states, according to the ACLU.

The fact that these rights were offered in a country as collectively conservative-thinking as India may be a head-scratcher. Upon looking back on history, however, it’s less confusing.

India, after all, was its own living, breathing culture both before and after the British came and went, and so there are fundamental aspects trickling down to this day that make the routes it takes different.

The recent Goethe-quoting, Shakespeare-analyzing Supreme Court judgment reinforces this: transgender Indians, for example, were openly respected historically, before the shadow of imperialism and all its new laws descended. Each country has a different history, and India’s own historical context simply paved the way for a different route towards increasing LGBT rights in the country.

If there’s anything or anyone India is playing catch-up to, it’s not to the West, England or America included. India is chasing after its own past, at least in terms of the law. It’s now up to the rest of its society — the transfixed audience — to join in the marathon of rights for a true victory.