The Ripple Effect: No confidence, and the crushing irony of promise-keeping

Theresa May has backed herself into a corner, but it’s not all her fault

Photo by Aishwarya Jayadeep

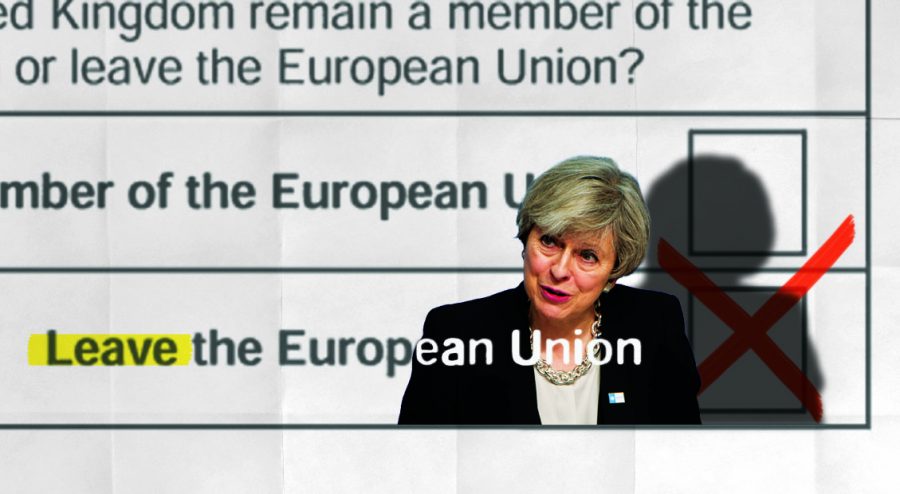

UK Prime Minister Theresa May’s proposed deal with the European Union to help facilitate Brexit suffered a historic defeat in the House of Commons, with a 230-vote margin.

“T

hat this House has no confidence in Her Majesty’s government.”

The words are mysterious. They sound like they belong in a James Bond movie. And they’re weirdly, eloquently pithy.

But they’re not as cryptic as they seem. No, they’re just the wording of a no-confidence motion in UK politics that challenges how well-supported the government, including the prime minister, is within its legislative body, the House of Commons. And today, such a no-confidence vote almost ousted Prime Minister Theresa May and her government.

Almost. But May and her vision of Brexit is still hanging on by a thread.

Indeed, this week hasn’t been amazing for the prime minister. Yesterday, her proposed Brexit deal was slapped down with a history-making, record-shattering 230-vote margin in the House of Commons, making the future of the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union even more queasily uncertain than it already was. Immediately after the crushing blow to plans that had been two years in the making her opposition called for a no-confidence motion to be scheduled.

Having survived that, her options are to debut an alternate deal with the EU that’ll win 230 people back over by Monday, or ask for an extension of the March 29 withdrawal deadline.

This wasn’t May’s first time facing the no-confidence showdown: in December, her own Conservative Party voted on their support for her as party leader. In fact, her resilience is mystifying — the fact that she’s politically intact after dodging all these bullets confounds both me and the numerous news headlines that called yesterday’s vote everything from a ‘historic humiliation’ to ‘dead as a dodo.’

But the question remains as to how many concessions can happen within the next week when she sees it as her duty to carry out the wishes of the majority of British people who voted in favor of Brexit three years ago. From May’s perspective, the boxes she must tick in making a deal must match all the boxes implicitly ticked by ‘LEAVE’ voters in the 2016 referendum: ending free movement between the UK and the European continent and regaining power over legislation and trade while still keeping on good terms with the EU.

How, then, is a leader trying so hard to respect this ‘solemn promise’ — her legacy as a leader — stumbling so close to losing the faith of the people?

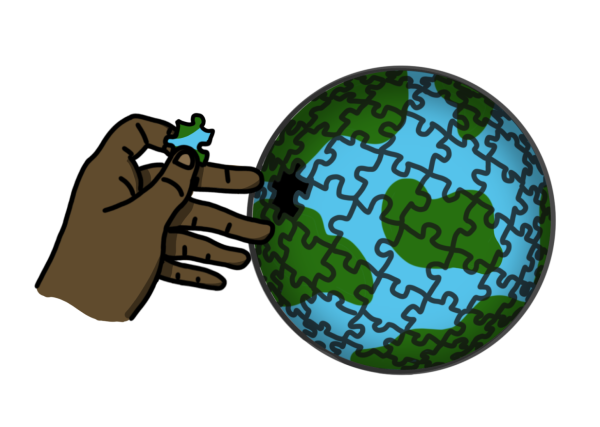

The answer lies in Plan A — namely, in the fact that there never was a Plan A to begin with. Apart from the ‘LEAVE’ and ‘REMAIN’ campaigns’ talking points, an actual plan for leaving the European Union didn’t exist. Voters in the Brexit referendum voted for leaving or remaining without fully knowing what one or the other would entail. As a result, Brexit consequences ranging from changed garbage collection practices to leaving a nuclear regulatory body weaseled through the cracks, undiscovered until after the vote.

The broad concepts voted for — leaving or remaining, Brexit or staying — certainly had some loose common threads stitched together by their respective campaigns: ideas like leaving the EU to regain control over the country, over immigration, over money abounded. But the blank space between those ideological threads was filled in freely, with people conjuring up a sans-EU United Kingdom in ever-so-slightly different ways.

Donald Tusk, the president of the European Council, recently tweeted that there’s a possibility of “a deal [being] impossible, and no one wants no deal.” He’s right: Brexit is at an impasse, all because satisfying the imagination isn’t so easy.

Without an established proposal for a ‘leave’ deal — a common baseline to have voted on in 2016 — there is no plan now that can live up to those that took up residence in people’s imagination three years ago.

A leader cannot make a promise without knowing what it entails. And neither can the people choose something without being fully informed of the consequences. It’s a pattern visible in elections and referendums worldwide: misinformation, a lack of information or even misapplied information at the ballot box leads to anger and confusion over broken promises, all because everyone had different visions of the promises at hand.

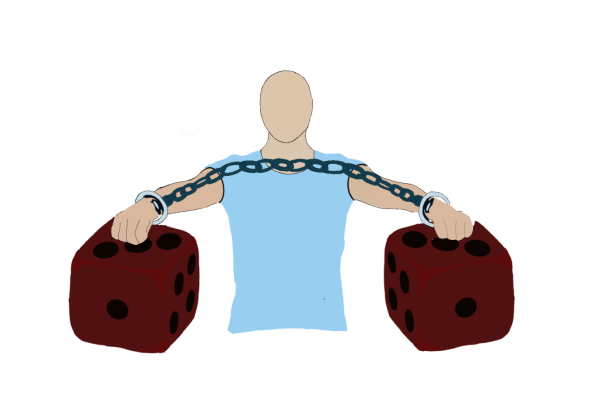

You cannot bind yourself to uncertainty, whether you’re the person in charge responsible for spinning something out of cottony vagaries, or whether you’re the person hoping that the rickety toothpick-and-tape construction of wishes in your head matches what plays out in reality.

But that structure of uncertainty is what’s ensnared Theresa May, in her commitment to a promise no one knew the exact terms of. There are few moves to make without toppling the whole thing down.