The Ripple Effect: Hatred vs. an oath of office

What it takes — and doesn’t take — to lead after a tragedy

Last Friday, attacks on mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand resulted in the deadliest mass shooting in the country’s recent history.

Now, there are a variety of ways world leaders can respond and have responded to such a situation in their own countries. The most common reaction is a litany of empty promises — promising to act, promising to change, promising that such a thing will never happen again despite a lack of concrete plans to avoid it. But another common route leaders take involves sweeping up the newly-sprung fear and striking out at the nearest possible target.

Case in point: Australian senator Fraser Anning, who blamed the New Zealand shootings on the immigration of “Muslim fanatics” — rather than the racist sentiments truly responsible.

Indeed, in times of crisis, vitriol often arises in full force among those in power with the most status to lose. But New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, however, has taken a completely different approach. While she has promised change so far, those promises haven’t been so empty. In light of the fact some of the weapons the Christchurch shooter used were semi-automatic guns — sometimes referred to as assault rifles — Ardern implored people to turn in their firearms as changes to gun laws were in the works.

By Tuesday, dozens had already been turned in.

37 guns out of 1.2 million may not seem like much, but it’s a start. Ardern’s vow to implement gun law reform within 10 days has already seen follow-through, considering the proposed ban, announced today, on all “military-style semi-automatic rifles” in the country. Coupled with her rhetoric focused on “fixing” the problems — virulent violence, white supremacists and so forth — as opposed to a call for further violence to “fight back,” Ardern seems to be one of the few world leaders most poised to actually make an impact for the better in the wake of tragedy.

But for all Ardern has done well in her handling of the situation so far, I do still quibble her statement that the actions of the shooter are “not us.” As much as we can hope to separate such cruelty from the majority, filtering out the bad with a sieve of morality, hatred is intrinsic somewhere within any group so long as fear exists to propel it.

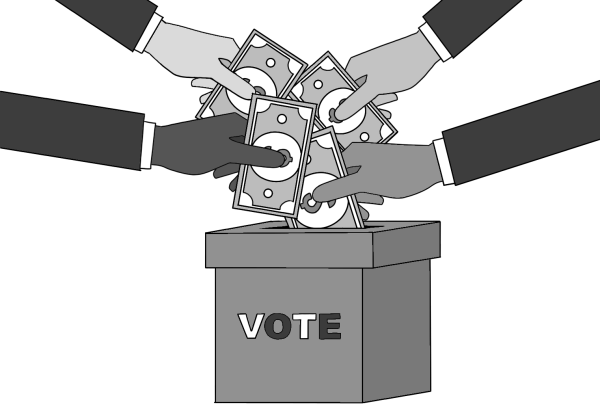

Fear lingers. Fear insinuates itself into society until it rots into hatred. And then — and then! — fear becomes the basis for a political platform through which hatred can take a stab at the oath of office.

We’ve seen this rhetoric waltz its way into the leadership of countries all around the world, and also in our own. It’s a self-reinforcing cycle: as one person with these ideals steps up into power, others think such prejudice is more acceptable and support further such leaders, allowing for more to emerge. And so on, and so on.

We can’t always reason with prejudice, that’s what the series of hate crimes over the course of recent years has clearly shown us. Hatred of the unknown is different from hatred caused by willful ignorance — the former can be educated out. The latter usually can’t.

But we can’t give up, either. When that kind of toxicity appears in so-called leadership, we must continue to try to keep it in check. Simple acts, from pointing out microaggressions that make others feel unwelcome to shutting down hostile speech, are what break down the support base for potential hateful leaders trying to rise up.

We’ve deified politicians, celebrities, everyone with an amplified voice in our society, when they, too, are stumbling in the dark. Before they blindly stumble across the putrid platform of hatred and hoist themselves onto it, we have to kick that platform out from under their feet and break the cycle.