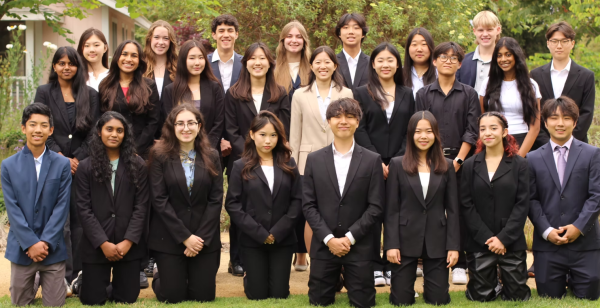

Diya Agrawal: the girl behind the wheelchair

Photo courtesy of Diya Agrawal.

“It happened recently, actually, some group mates of mine in the assignment were … I wouldn’t say blatantly leaving me out, but it was kind of like ‘you can have the leftovers, you can have the leftover assignment, we can make jokes about your disability … like oh, haha I wish I was paralyzed’ and I’m not paralyzed at all!” freshman Diya Agrawal said. “I have cerebral palsy.”

Agrawal is one of the 17 million children born with cerebral palsy, a condition which Agrawal said “makes all of the muscles in your body very tense, all the time.”

According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, most cases of cerebral palsy occur in early childhood and cause a number of permanent movement complications.

Cerebral palsy was a label Agrawal was unwillingly forced to fit into her definition of herself.

“I come off as reserved, too serious, people think I’m stupid,” Agrawal said. “Sometimes it’s harder to get your personality across when people first see your wheelchair and then see you.”

Shattering the dreggy lenses of ignorance is Agrawal’s unshaken confidence. Proud to stand up for her opinions, Agrawal said she has grown strong above all the attempts to make her weak.

“It might come off harsh, it might come off brutal, but at least you got your point across and that’s what I tend to do now,” Agrawal said.

Agrawal’s emotional and mental growth did not come without complications. Agrawal said she has struggled with facing biased judgment all her life.

Once, she was barred from attending a friend’s birthday party because the parents did not feel “comfortable” having a kid in a wheelchair around.

“If I broke your friend’s leg and I put her in a wheelchair, would you uninvite her to the party just because her leg is broken or would you find a way for her to come with others?” Agrawal said.

Agrawal´s childhood difficulties consisted of more than just handling the emotional injuries she was constantly subjected to; consistent physical therapy is crucial for diffusing the effects of the condition. She said she admits that, as a child, it was troublesome to comprehend the necessity of trying to achieve something seemingly impossible: walking.

“I would fall and I would get upset … that I’m falling,” Agrawal said. “They pick me up and put me back to square one and I [would] keep falling and I [would feel like] I’m getting nowhere.”

As scary as it might be to fall flat on your face, Agrawal said there will always be a helping hand waiting. With its unique atmosphere, Junior Sports Camp has welcomed Agrawal into a community united by courage.

“That was the one place where I was fully taken care of,” Agrawal said. “There wasn’t question of ‘Can we do this? ‘Can we not do this?’ It was ‘We’ll figure out a way to do this.’ It was ‘Let’s keep going.’”