Racial stereotypes have been proven to invoke reduced expectations and heightened pressures for students in affected groups. Not only that, but these racial stereotypes also contribute to the achievement gap, or set of disparities in testing scores, between Asian and white students versus non-Asian minorities, according to the National Education Association.

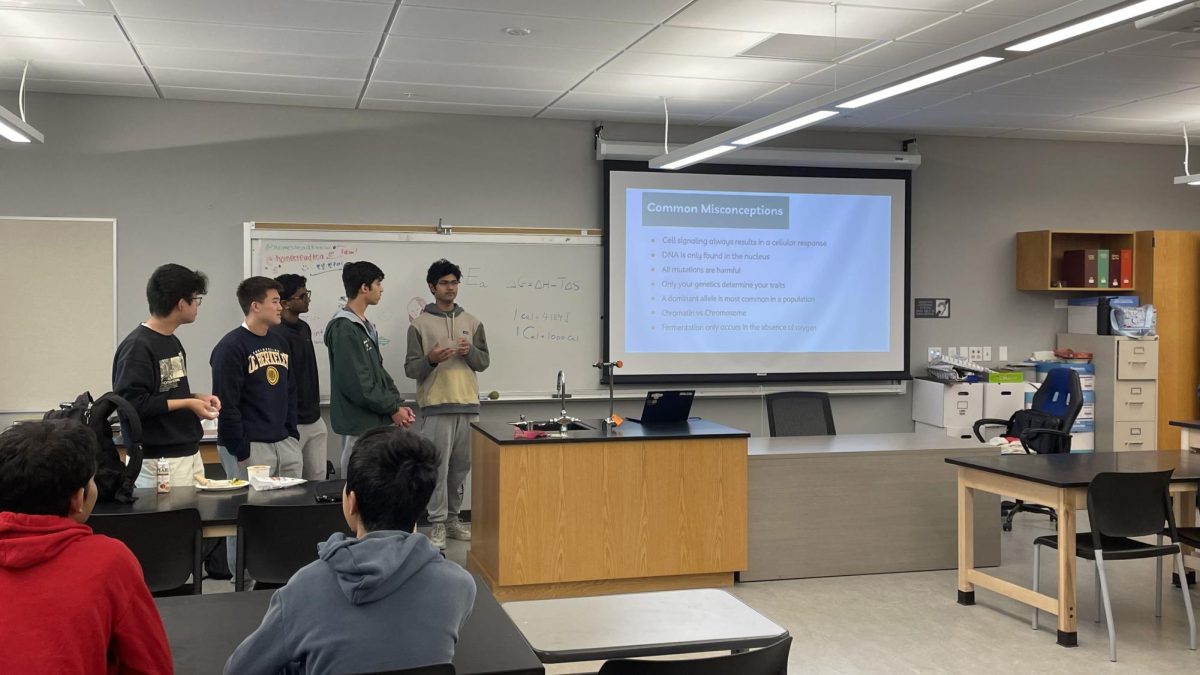

As diverse and accepting of a campus HHS is, it is still not spared from this issue. According to an editorial done in print issue four of The Epitaph, the racial makeup of HHS (73 percent being Asian or Caucasian, 27 percent other) is not consistent in AP and honors level classes.

The achievement gap is not limited to distinctions between different racial groups but also gender and socioeconomic factors. According to an article in US News, the achievement gap between black and white students has improved little over the last 50 years.

Previously, 87 percent of white students in their senior year of high school outscored black students also in their senior year. According to the article, black students placed in the 13th percentile of the score distribution for their white counterparts.

Currently, black students place in the 19th percentile. It has been estimated that should these low rates of change continue, the gap in mathematics between the two groups will be closed only after two and a half centuries. The fact that black students have to wait 250 years for the gap to be closed is ridiculous.

Nationwide, black and Hispanic children account for 37 percent of students. Within this 37 percent, only 27 percent take at least one AP class. Location is another factor in this disparity. Black, Hispanic and Native American students are more likely to live in areas with schools that do not offer advanced courses.

According to a study done by School Psychology Quarterly, teachers viewed black students with lowered expectations and disproportionately refer black students to special education and disciplinary action as compared to their white counterparts. Regardless of high academic standing, black students were given less attention.

Students who are victims of this bias have not only been found to have lower grades, but also a lowered motivation to excel.

The stereotype of black students as “troublemakers” manifests in harsher punishments are doled out by teachers after two infractions due to the belief that this bad behavior is likely to continue. Black students are therefore three times more likely to be suspended and expelled.

If a student is continually led to believe that academic success is not inherent in their racial identity, how can they be motivated to exceed academically? Not to mention, if a student is placed with lowered expectations immediately, it is harder to deviate from these ingrained expectations.

For black and Hispanic youth, the desires to prove stereotypes wrong, or even simply the knowledge of these stereotypes, causes the body to produce more stress hormones as a form of a “coping mechanism.”

According to a study done by Educational Theory, the resilience within successful black students to overcome negative stereotypes manifests into a greater issue of a mental health crisis.

According to the author, “black students work themselves to the point of extreme illness in [an] attempt to escape the constant threat of perceived intellectual inferiority.”

A phenomenon dubbed the “stereotype threat” describes the impact of stereotypes on a student’s development of their identity and intellect. Black students were found to underperform on tests that were not “diagnostic of intellectual ability” due to the “priming” of negative racial stereotypes. Asian students were found to have lowered concentration skills and performance on quantitative skills test due to the “priming” of so-called positive stereotypes such as their presumed adeptness in mathematics.

Moreover, although Asian Americans are not negatively impacted by the achievement gap, racial stereotypes still come into play. Asian American students were viewed as “cooperative” and more successful academically, as per the “model minority” stereotype.

The model minority myth is described as a “cultural expectation” on Asian Americans. Perhaps the most detrimental aspect of the myth is the assumption that Asian Americans are never in need of assistance. The impacts of this is that Asian Americans are less likely to report issues of stress and hopeless feelings, yet not seek help from a counselor.

Asian Americans may be successful (for example, compared to their white counterparts, Asian Americans have a higher percentage of individuals with a bachelor’s degree or higher) but these high-achieving statistics mask groups who do not reflect the ideals of the model minority stereotype imposed upon them.

Teachers have been found to be three times more likely to expect their Asian American students to go to college. But 10 percent of Laotian Americans, 13 percent of Hmong Americans and 16 percent of Cambodian Americans in California have some of the lowest attainment of college degrees. In addition, Hmong and Cambodian Americans live in poverty at higher rates than black and Hispanic individuals. These statistics are said to be masked by Chinese and Indian Americans, and as such, is not an accurate reflection of Asian Americans.

As an article in The Atlantic puts it, “The consequences are classrooms where Asian students not excelling in math are seen as an oddity, and black students excelling in math are seen as an outlier.” The stereotypes placed onto these two groups have very real effects, and are more than just unfortunate statistics.

There are countless students who feel as though they may never amount to anything, or inversely, students who feel inadequate because they do not fit into the “mold” of what is expected.

Asian and black individuals are on opposite ends of a spectrum where negative stereotypes are place on to black people and more “positive” ones are placed onto Asian individuals. In the end, both stereotypes have a negative effect.

We as a whole need to understand that different groups are subjected to different barriers in their success. It is useless to place blame on certain groups for the achievement gap. Stereotypes may always linger, but your choice to partake in the belief and perpetuation of these stereotypes is dependent on yourself. Stereotypes are more than just unfortunate statistics, but have real-life impacts that need to be recognized.