STAFF EDITORIAL: Schools should not overstep their jurisdiction

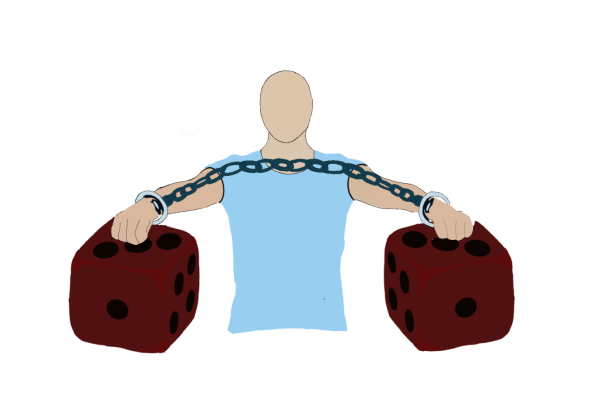

It all started as a game.

Created by two seniors, each player in “Homestead Assassin” is randomly assigned a target, a student they are meant to “assassinate” with a nerf gun or water balloon before the established deadline.

After the target is eliminated, they move on to the next round — with the new target being the target of the person they just eliminated — until the last person standing has a chance of winning the pool of money collected as an entry fee.

On Feb. 12, less than a week into the game, administration shut it down, as the game “violates school rules and raises serious safety concerns,” principal Greg Giglio said in an email addressed to students.

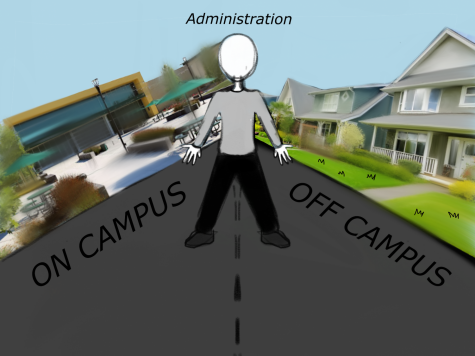

However, because the game had been taking place after school hours and was played off-campus, it should not be subjected to school rules.

The creators of the game, in a now-defunct website, clearly stated in their guidelines that the game must be played off-campus and stated that it was not affiliated with the school.

According to the HHS website, school rules only apply to students during school hours and during school-sponsored events both on and off campus, including sporting events, dances and club activities. School hours include travel time to and from school.

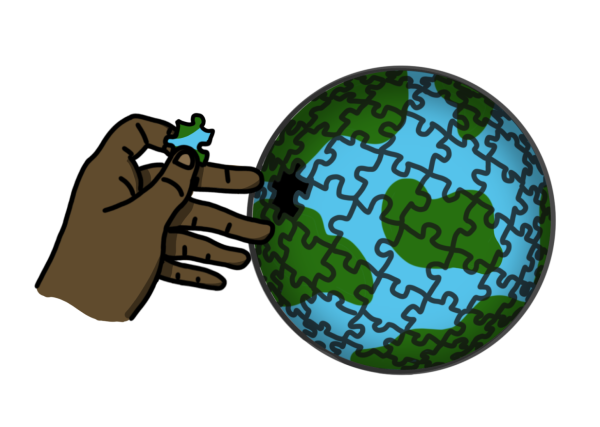

If that is so, then the school has no jurisdiction to regulate on off-campus, non-school sponsored activities like “Homestead Assassin.”

The game had been occurring after students arrived home after school and on the weekend. Since it was being played off-campus and during students’ recreational time, there is no way the game infringes on school rules.

By defining this game as a violation of school rules, the administration shows just how arbitrary the line is between on-campus and off-campus activities.

Administration must establish a clear line in its rule over where its jurisdiction lies in regulating off-campus activities.

In fact, the fundamental rights of students beyond school grounds and school-sanctioned activities cannot be subjected to school authority, and doing so infringes on a student’s first amendment rights.

In the 1969 landmark decision Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, Iowa students wore black armbands to their public school as an act of protest against the Vietnam War, but days after they did, the school forced the students to remove their armbands or face suspension.

The court ruled that the school’s behavior violated the students’ freedom of expression.

“School officials do not possess absolute authority over their students,” Justice Abe Fortas said in his reasoning. “Students in school, as well as out of school, are ‘persons’ under our Constitution. They are possessed of fundamental rights which the State must respect, just as they themselves must respect their obligations to the State.”

The game had been occurring after students arrived home after school and on the weekend. Since it was being played off-campus and during students’ recreational time, there is no way the game infringes on school rules. By defining this game as a violation of school rules, the administration shows just how arbitrary the line is between on-campus and off-campus activities.

If administration can force the closure of an off-campus activity due to potential safety concerns, it creates a perplexing precedent into how other activities should be seen by administration.

It broadens the scope of the school’s ability to limit activities just on the basis that safety concerns may arise although no actual repercussions have yet to occur.

Then, would the school be allowed to regulate house parties as well, where illegal and potentially dangerous activity may occur?

The concerns administration has over the game are valid, citing previous injuries and violations of state and city laws by players from other schools. However, until this game produces a justifiable repercussion, the school is hasty in banning it, especially with such serious consequences for students involved, should they decide to play it again.

After all, administration is “not aware of anything serious happening in the Homestead version,” Giglio said himself, in his email.

Stating that students caught playing the game again will be subject to suspension and a loss of senior privileges is extreme for a game likely created not out of malice or ill-intent, but as a way for seniors to have fun in their last year.

And where is the line drawn? If students choose to play the game off campus on the weekend, for example, and news of the game revival gets back to administration, will the consequences be upheld? And if they are, is that a direct violation of students’ first amendment rights?

Furthermore, administration was not transparent enough in outlining the exact aspects of the game that violated school rules. Which rules, exactly, were being violated?

Administration should have also actively listened to students instead of shutting them down entirely, especially when they have little authority to ban a student’s off-campus activities.

Administration could have worked with the creators to modify the game to eliminate any on-campus concerns, or even simply issued a warning to let students know they were aware that game was being played. Then, they would have been within their rights to enact stricter measures in the event an actual injury or violation did occur.

Concerns about the potential dangerous nature of the game should be a parental concern, not the concern of the school. If students break the law while playing the game, then law enforcement should step in. The school has no reason to take disciplinary action, unless the game is being played on campus or causes a substantial disruption to school activities, as stated in the Tinker ruling.

If administration is concerned about the game itself, then it is reasonable to issue a warning, but when an activity such as this is occurring off campus, in no way should the school regulate the game, force its closure or forbid its revival.